This post is written by Aaron Balick: Dr. Aaron Balick is a psychotherapist, cultural theorist, media consultant, and author of The Psychodynamics of Social Networking: connected-up instantaneous culture and the self. Aaron has a passion for taking psychological findings from the clinic and the academy and transforming them into ideas that can be applied to individuals, organisations and culture. He is also an active communicator and international speaker, a writer for publications including Wired, The Huffington Post, The Guardian and a regular contributor on BBC Radio and Children’s BBC television. He is the author of the children’s self-help book Keep Your Cool: how to deal with life’s worries and stress and the forthcoming The Little Book of Calm: tame your anxieties, face your fears, and live free. Aaron is the director of Stillpoint Spaces London, a psychological hub and think-space based in Clerkenwell.

Here Aaron Balick has written about why he has chosen to host a talk on the mind of Donald Trump on Tuesday 5th December. Click here to get tickets to his talk.

“When I was growing up there were two common ways of defending yourself from verbal insults in the playground. The first was a simple, “I know you are, but what am I?”, which could be repeated interminably in response to a litany of insults. The slightly more poetic version was “I’m rubber and you’re glue, whatever you say bounces off me and sticks to you.” Both are equally ineffective, but the second is more pleasant to the ear.

In psychology, we understand a response like this as an ego defence. These are ways in which we protect ourselves from being psychologically injured by others. In this case, these tactics use a defence we call projection. Instead of taking the insult to heart, it is projected straight back on the other. “It’s not in me,” says this defence, “it’s you.”

Projection is a “primitive” defence because it involves splitting the world into black and white; attempting to keep all the good inside oneself and the bad in other people. This is useful when you are a child and your ego is still vulnerable and developing. As you grow older, and your ego feels more secure, there’s less need to resort to primitive defence.

For those who have not developed a secure ego, these defences can cause havoc because they are often deployed even if the ego isn’t under attack. This happens when a person with an insecure ego perceives they are under attack when in fact they are merely being challenged, criticised, or even just disagreed with.

Donald Trump frequently demonstrates primitive defences, often resorting to Twitter to deploy them. This indicates what we might call a weak or insecure ego that requires ardent defending – not an ego that can handle nuance, criticism, or rejection. When a baby throws its toys out of the pram, it’s because its fragile ego simply cannot handle the frustration of a “no”. Teenagers may kick up a fuss at a “no” but they are also much more likely to bargain, compromise, or charm their way to a “yes”. By all accounts, Trump’s emotional age has not achieved adolescence. As he’s over 70, it’s not likely it will.

As if this wasn’t bad enough, Trump is also impulsive, a trait exacerbated by his attachment to Twitter. His Twitterstorms are a testament to his psychology, listing those whom he perceives enemies while diminishing them with ad hominem childish nicknames (Crooked Hillary, Lyin’ Ted, Little Marco, Crazy Bernie, etc.). He does the same with “the failing New York Times” or “the Fake News Network [CNN]” which enables him to maintain a warped internal reality unimpinged by the concerns or opinions of others which he deems to be simply false.

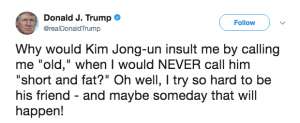

This is clearly unpresidential and bad enough domestically, but this impulsivity becomes even more dangerous internationally. Needless to say, taunting a nuclear-weapon-wielding foreign leader with a track record for his own impulsivity is not wise for anyone:

Trump’s impulsivity alongside his lack of capacity for nuance is dangerous because it reduces his capacity to meet the complexity of his office. Additionally, his proclivity to seek adulation as a first priority – something his base appears to wish to give him in unlimited quantities – impairs his judgement in relation to making decisions in the national interest (not just his own).

Understanding Trump’s psychology is not a question of whether he is mentally ill or not. It is a matter of understanding how his personal psychology manifests itself in relation to the office he occupies. The presence or not of mental illness alone is not an indicator of whether someone is good or bad, or can do a job or not. However, one’s behaviour, as driven by his or her psychology, is of interest to us all when such a psychology occupies the highest office in the land.

Click here to get tickets to Aaron’s talk – Inside the Mind of Donald Trump on Tuesday 5th December.