This is a guest article by Dr. Chris Copperwheat . Chris is the Liverpool Telescope Astronomer-in-Charge at the Astrophysics Research Institute of Liverpool John Moores University. If you would like to hear more. Book your tickets to his next talk with this link

Will We Discover Aliens in Our Lifetime?

Since the early days of humanity, a fundamental question has been ‘are we alone in the Universe?’. The search for life beyond the Earth is one of the key topics in modern astronomy. It is a question which transcends science: the discovery of alien life would shake our civilisation to it’s core. We would be forced to question our understanding of what it is to be human, our place in the Universe, our religious beliefs: the list goes on. In confronting these questions there will be an opportunity for us to grow as a species. Most excitingly, our progress towards this goal is advancing at such a rate that there is a very real chance that this discovery will happen within our lifetimes.

So why do I think this is so? The answer is that for the first time in the history of humanity, we are establishing where to look, and we are building the tools to do so. The Universe is a big place, and if there is life out there, it isn’t screaming for our attention. Our exploration of the planets and moons in our own Solar System with robotic probes have turned up no evidence for life to date, although we still hold out hopes for the discovery of simple microbial life in the icy moons of the outer planets. Enceladus for example, one of the moons of Saturn, contains a vast ocean between its icy surface with conditions which may be similar to those in the oceans of Earth; with organic molecules and hydrothermal activity providing the energy source for microbial life. For more complex life it seems we have to look beyond the Solar System to other stars, but `scattergun’ approaches such as the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI), in which the entire sky is scanned for radio signals with a non-natural origin, have so far produced no results.

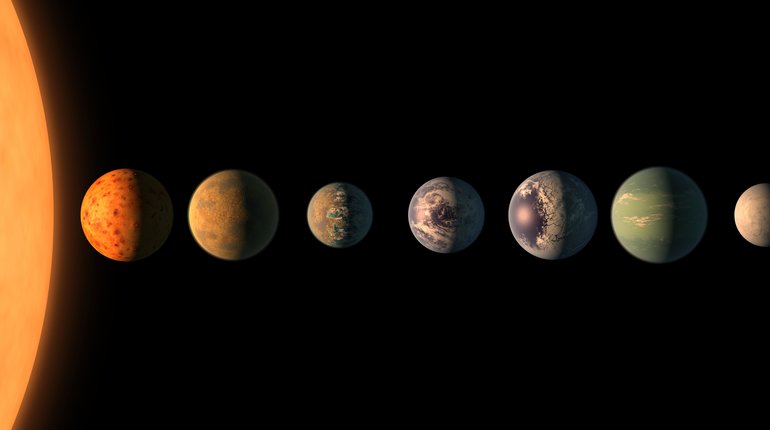

Things are changing with the new field of exoplanet science. When I was at school in the 1980s, the only planets we new of were those orbiting our own star, the Sun. The first planet around another star was discovered in the 90s, and now we know of thousands. Even more exciting is that as we refine our observing techniques we are starting to find smaller and smaller planets. The first discoveries were large, gaseous bodies like Jupiter. We now know of an increasing number of planets which are Earth sized, and at a distance from their star such that the surface temperature allows for the presence of liquid water. While for all we know it might be possible for life to exist in a huge variety of environments, the one thing we know for certain is that it can exist on wet, Earth sized planets. This then, is the first place to look for `life as we know it’. The next generation of large space and ground based telescopes will be able to make a detection of the atmospheres of these Earth sized worlds. We will be looking of course for signs of the same oxygen/nitrogen rich atmosphere we enjoy on Earth. There may be even more to discover. We know that we are having an impact on the atmosphere of our planet through the burning of fossil fuels. Some theoretical studies have suggested we may be able to detect such pollutants in the atmosphere of an alien world, such that we could point to a planet and say not only does it house life, but life which has gone through an industrial revolution. This is a staggering thought!

Before getting carried away though, we must stand back and look at the big picture. The physicist Enrico Fermi pointed out the contradiction between our current lack of evidence of alien life and the high probability of it existing through simple mathematical arguments. The so-called Fermi paradox asks the question ‘where is everybody?’. The mathematical argument boiled-down is this: our Galaxy alone contains around 400 billion stars. Even if you make pessimistic guesses as to the number of stars with planets around them, the number of those planets that can support life and the number that actually do support life; you still end up with thousands to millions of life forms in our Galaxy, simply because you are starting with such a large number of stars. This idea was expressed powerfully by Frank Drake in 1961 with his famous Drake Equation. So where is everybody? There are a number of possibilities. Maybe they are all around us, but we are too primitive to detect them. Are ants able to comprehend that their anthill is situated next to a major motorway? Maybe aliens are too alien for any hope of communication: consider for example a species which takes a million years to utter a single sentence. The radio signals would seem like background noise to us. Or perhaps they are deliberately not contacting us. This could be for benign reasons: the crew of the USS Enterprise in `Star Trek’ are forbidden from contacting more primitive life forms lest they influence their natural development. Or maybe life in the Universe is quiet for reasons of self-preservation: perhaps there are some scary, super-predator species out there, and the sensible option is to keep quiet.

There is another possibility: perhaps we are alone. Perhaps there is something which makes the existence of intelligent, communicating, space-faring life incredible unlikely. This concept is sometimes referred to as `the Great Filter’. The idea is that life begins, but at some point it hits a stumbling block, and the chances of it overcoming that block is billions to one. Thus most life forms reach that point and go no further. This leads to a big question for human beings: if this line of logic is correct, then is the filter in our future or our past? It could have happened in our past – perhaps a step in our evolution, such as the development of human intelligence, was staggeringly unlikely to have occurred. Thus we are the winners in the lottery of life, and the inheritors of the Universe. But perhaps the filter lies in the future? Perhaps many species make it to the same point as us, but then wipe themselves out with their own technologies and destructive nature. If so, the picture for humanity is bleak. If an empty Universe means that no aliens so far have overcome that hurdle, it is unlikely in the extreme that we will either.

This is a disquieting thought, but we should not get hung up on such thought experiments. We are a young species. The search for life has not been going on for long. We do not see far, and there is so much we do not understand. As I said when I began this article, more than at any previous time in human history we have the ability to address the question of the existence of life beyond the Earth. We are starting to know where to look, and we are building the tools to do so. We should approach this task with a sense of hope and wonder: great discoveries are at hand, one way or another. These explorations speak to something fundamental in us as human beings: we seek this knowledge because we are enriched by the answers, by what it tells us about ourselves and by the search itself. The search for alien life is fundamentally the search for our own humanity.

If you would like to hear more from Dr. Chris Copperwheat, you can book your tickets to his next talk with this link.